Attending to Remember

How the Rhythm of Our Focus Shapes Our Memories

We’ve all been there. You walk into a room and suddenly stop, paralyzed by a simple, frustrating question: Why did I come in here? Or perhaps you are driving, intent on finding a specific street sign, only to have a dog run out between parked cars, shattering your focus.

These moments highlight the delicate dance between two fundamental cognitive forces: attention and episodic memory.

In a recent paper published in Current Directions in Psychological Science, my colleagues and I explore this intersection. Titled "Attending to Remember: Recent Advances in Methods and Theory," we dive into the latest cognitive neuroscience research revealing how the quality of our attention – down to the millisecond – dictates whether we learn and remember, or whether those moments slip away [1].

Here is a brief look at the core concepts we cover in the article, and what they tell us about the human mind, learning, and remembering.

Two Sides of attention

To understand memory, we first have to look at how we attend to the world. In the article, we highlight a long-argued dichotomy between top-down and bottom-up attention.

- Top-down attention is goal-directed. It's the mental spotlight you turn on when you are scanning for that specific street name.

- Bottom-up attention is stimulus-driven. It's what happens when that dog runs into the street – your attention is captured by the unexpected event.

Though, it's critical to emphasize that these systems don't work in isolation. Rather, they interact dynamically with our goals. In the article, we highlight that the interactions between these attention networks and our memory systems are bidirectional: not only do our goals influence where we focus our spotlight of attention, but what we attend to also reshapes our goals.

Readiness to Remember

One of the most exciting developments in our field is the ability to measure a person's "readiness" to learn or remember before they even see the information or express their memory for the information [2].

Using psychophysiological tools like pupillometry (measuring pupil diameter) and scalp EEG (tracking electrical brain activity), we can now see that the state of your brain just prior to an event predicts memory success. For example, prior work from our lab on goal-directed memory published in Nature revealed that the size of a participant's pupil—and their brain’s posterior alpha power — in the 1-second period just prior to receiving a retrieval goal predicted whether they would successfully remember the item associated with that goal in a prior learning phase [3].

In other words, we can think of sustaining attention as more than just a switch you flip on and off; rather, it's a fluctuating state that prepares an individual for successful acquisition and expression of knowledge.

Fig. 1. Assessing the influence of attention on memory retrieval. Shown in (a) are the frontoparietal networks of attention and cognitive control derived from network parcellations computed from the full sample (N = 1,000) in Yeo et al. (2011). The schematic of the goal-directed memory-retrieval task used in Madore et al. (2020) shows (b) that pre-goal lapsing was measured using EEG posterior alpha power and pupil size in the last 1 s of the ITI, whereas goal-coding strength was measured using a retrieval goal-cue-locked ERP extracted from a midfrontal cluster of electrodes. In (c) the 1 s prior to the onset of the retrieval goal cue, pupil size (and posterior alpha power; not shown) significantly correlated with retrieval success, and midfrontal EEG goal-coding strength partially mediated this effect (n = 75; Madore et al., 2020). DAN = dorsal attention network; VAN = ventral attention network; CCN = cognitive control network; ITI = intertrial interval; ERP = event-related potential. Created in BioRender. https://BioRender.com/mejp1fu.

Fig. 1. Assessing the influence of attention on memory retrieval. Shown in (a) are the frontoparietal networks of attention and cognitive control derived from network parcellations computed from the full sample (N = 1,000) in Yeo et al. (2011). The schematic of the goal-directed memory-retrieval task used in Madore et al. (2020) shows (b) that pre-goal lapsing was measured using EEG posterior alpha power and pupil size in the last 1 s of the ITI, whereas goal-coding strength was measured using a retrieval goal-cue-locked ERP extracted from a midfrontal cluster of electrodes. In (c) the 1 s prior to the onset of the retrieval goal cue, pupil size (and posterior alpha power; not shown) significantly correlated with retrieval success, and midfrontal EEG goal-coding strength partially mediated this effect (n = 75; Madore et al., 2020). DAN = dorsal attention network; VAN = ventral attention network; CCN = cognitive control network; ITI = intertrial interval; ERP = event-related potential. Created in BioRender. https://BioRender.com/mejp1fu.

The Rhythm of the Mind

Perhaps the most counterintuitive finding we discuss is that attention and memory are rhythmic.

Research suggests that attention samples the world in cycles, oscillating roughly in the theta (4–7 Hz) and alpha (8–12 Hz) frequency ranges. Think of it less like a continuous beam of light and more like a strobe light. There are "optimal" phases of this rhythm where we are primed to process information, and "sub-optimal" phases where we are less receptive.

This raises a fascinating question we explore in the paper: Does memory encoding and retrieval depend on the phase of this rhythm?

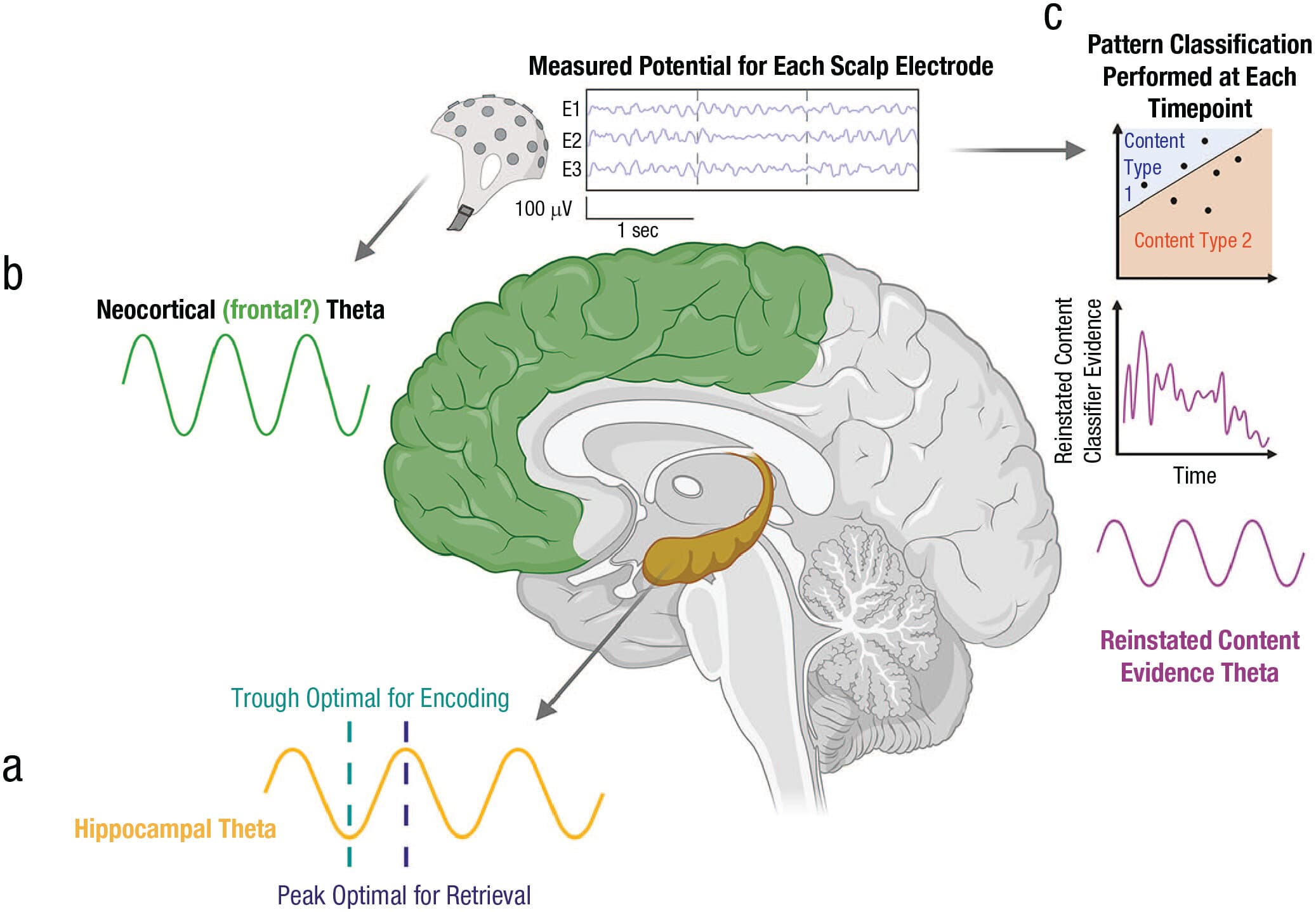

Recent evidence supports the "Separate Phases of Encoding and Retrieval" (SPEAR) model [4]. The theory posits that the hippocampus (the brain's memory hub) might switch between processing modes—taking in new information (encoding) versus generating internal predictions (retrieval)—in sync with these theta rhythms. We are beginning to see that the strength of memory representations in the neocortex actually oscillates, perhaps governed by these attentional clocks.

Fig. 2. Three types of modeled or observed neural theta oscillations. The schematic shows (a) the SPEAR model of hippocampal theta, (b) neocortical theta power (which may or may not relate to theta oscillations in the frontoparietal cortex and/or hippocampus), and (c) theta-specific oscillations in reinstated (i.e., retrieved) episodic content (as quantified by pattern-classifier evidence in neural data). SPEAR = separate phases of encoding and retrieval. Created in BioRender. https://BioRender.com/p71c406.

Fig. 2. Three types of modeled or observed neural theta oscillations. The schematic shows (a) the SPEAR model of hippocampal theta, (b) neocortical theta power (which may or may not relate to theta oscillations in the frontoparietal cortex and/or hippocampus), and (c) theta-specific oscillations in reinstated (i.e., retrieved) episodic content (as quantified by pattern-classifier evidence in neural data). SPEAR = separate phases of encoding and retrieval. Created in BioRender. https://BioRender.com/p71c406.

Aging and the Precision of Memory

As we age, our memory changes. But we argue that looking at simple "hit or miss" rates (did you remember the item or not?) misses the nuance. We need to look at memory precision.

In the article, we discuss paradigms where participants must remember continuous features, like the exact shade of a color on a 360-degree wheel [5].

Older adults often show a decline in this precision. This "blurring" of memory might be linked to neural dedifferentiation—a reduction in the selectivity of neural activity [6].

Crucially, this decline in precision seems partially attributable to changes in attention. When older adults are given cues to guide their attention, the gap in performance between them and younger adults narrows. This suggests that keeping our memories sharp is, in part, about maintaining the ability to filter and focus.

Fig. 3. Example episodic memory precision task. Participants encounter (a, top) objects shaded in one of 360 possible colors. Participants then encounter (a, bottom) a grayscale version of previously encountered objects and indicate their memory for the color of the object by clicking the corresponding color on the wheel. Illustrative distributions of (b) memory precision errors are mapped from the circular space to the linear space of −180 to +180. Here, young adults (blue dashed line) are schematized to demonstrate higher memory precision than older adults (solid red line). Created in BioRender. https://BioRender.com/n00n200.

Fig. 3. Example episodic memory precision task. Participants encounter (a, top) objects shaded in one of 360 possible colors. Participants then encounter (a, bottom) a grayscale version of previously encountered objects and indicate their memory for the color of the object by clicking the corresponding color on the wheel. Illustrative distributions of (b) memory precision errors are mapped from the circular space to the linear space of −180 to +180. Here, young adults (blue dashed line) are schematized to demonstrate higher memory precision than older adults (solid red line). Created in BioRender. https://BioRender.com/n00n200.

The Future: Closed-Loop Science

Finally, we look toward the horizon of closed-loop experiments.

Historically, we’ve relied on correlations—observing that when attention is high, memory is good. But new technology allows us to intervene in real-time. By monitoring a person’s brain state or pupil size millisecond-by-millisecond, we can trigger memory tasks exactly when the brain is in an "optimal" or "sub-optimal" state.

Imagine a system that detects when your attention is lapsing and waits to present crucial information until you are back "in the zone." This approach promises to move us from simply observing these relationships to demonstrating the causal links between how we attend and how we remember.

Fig. 4. Innovative techniques for real-time closed-loop interventions on attention (and cognition more broadly). Real-time causal intervention studies require constructing and validating a robust (a, left) trial-by-trial pipeline to measure, clean, evaluate, and act on psychophysiological assays in real-time, which then can be used to manipulate the stimulus display, such as that for an (a, right) adaptive memory task with real-time attention tracking and reorienting. Example approaches for the real-time evaluation of psychophysiological assays of attention include (b, left) pupillometry (c, left; e.g., pupil-size dilation or constriction that surpasses a real-time adaptive baseline pupil threshold), (b, middle) scalp EEG (c, middle; e.g., elevated posterior alpha power), and (b, right) functional MRI (c, right; e.g., pattern-classifier decoding of attentional state). Created in BioRender. https://BioRender.com/k46d189.*

Fig. 4. Innovative techniques for real-time closed-loop interventions on attention (and cognition more broadly). Real-time causal intervention studies require constructing and validating a robust (a, left) trial-by-trial pipeline to measure, clean, evaluate, and act on psychophysiological assays in real-time, which then can be used to manipulate the stimulus display, such as that for an (a, right) adaptive memory task with real-time attention tracking and reorienting. Example approaches for the real-time evaluation of psychophysiological assays of attention include (b, left) pupillometry (c, left; e.g., pupil-size dilation or constriction that surpasses a real-time adaptive baseline pupil threshold), (b, middle) scalp EEG (c, middle; e.g., elevated posterior alpha power), and (b, right) functional MRI (c, right; e.g., pattern-classifier decoding of attentional state). Created in BioRender. https://BioRender.com/k46d189.*

Final Thoughts

This paper represents a synthesis of where the field stands and where it is going. By understanding the mechanisms of attention—its rhythms, its neural signatures, and its role in aging—we get closer to understanding the machinery of our own minds.

You can read the full peer-reviewed article here: Attending to Remember: Recent Advances in Methods and Theory.

Stay tuned for more updates on the science of sustained attention.

References

- [1]Schwartz, S.T., et al. (2025). Attending to remember: Recent advances in methods and theory. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 34(6), 330-341. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1177/09637214251339452

- [2]Madore, K.P., & Wagner, A.D. (2022). Readiness to remember: predicting variability in episodic memory. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 26(8), 707-723. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2022.05.006

- [3]Madore, K.P., et al. (2020). Memory failure predicted by attention lapsing and media multitasking. Nature, 587(7832), 87-91. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2870-z

- [4]Hasselmo, M.E., Bodelon, C. & Wyble, B.P. (2002). A proposed function for hippocampal theta rhythm: separate phases of encoding and retrieval enhance reversal of prior learning. Neural Computation, 14(4), 793-817. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1162/089976602317318965

- [5]Sutterer, D.W., & Awh, E. (2016). Retrieval practice enhances the accessibility but not the quality of memory. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 23(3), 831-841. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-015-0937-x

- [6]Sheng, J., Trelle, A.N., Romero, A., Park, J., Tran, T.T., Sha, S.J., Andreasson, K.I., Wilson, E.N., Mormino, E.C., & Wagner, A.D. (2025). Top-down attention and Alzheimer’s pathology affect cortical selectivity during learning, influencing episodic memory in older adults. Science Advances, 11(24). Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.ads4206

Written by

Shawn Schwartz

Software engineer, researcher, and lifelong learner. PhD from Stanford, Ex-Slack Data Science. Building tools at the intersection of technology and science.

Subscribe to my newsletter

Get notified when I publish new articles. No spam, unsubscribe anytime.